Dublin Core

Title

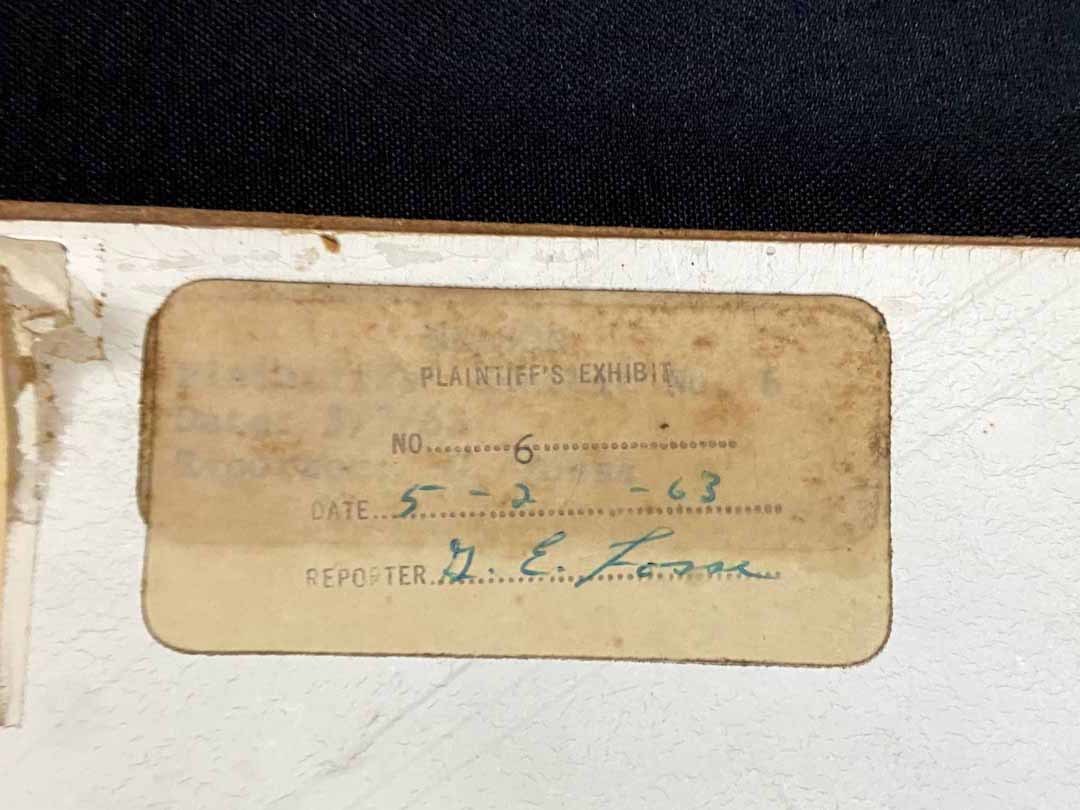

1958 Kaneland School Bus Crash: Law Suit and Plantiff's Exhibit Photos

Subject

Source: Molitor v. KANELAND UNIT DIST. NO. 302

24 Ill. 2d 467 (1962)

Supreme Court of Illinois.

Opinion filed March 23, 1962.

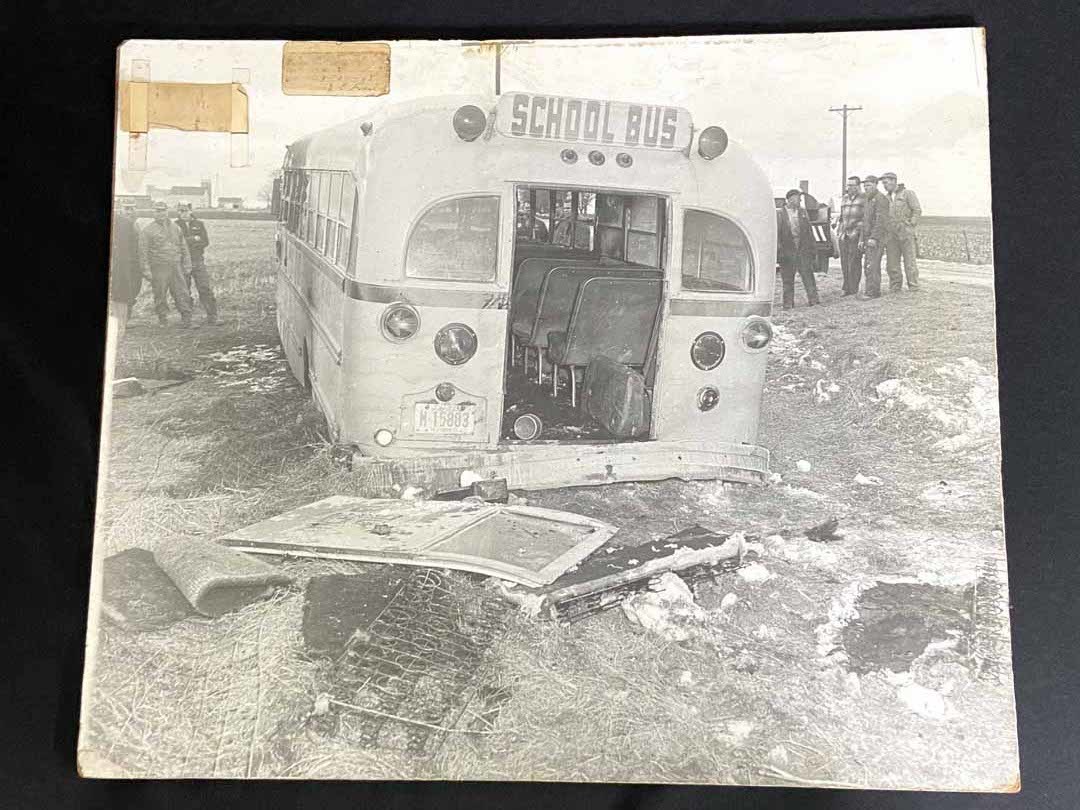

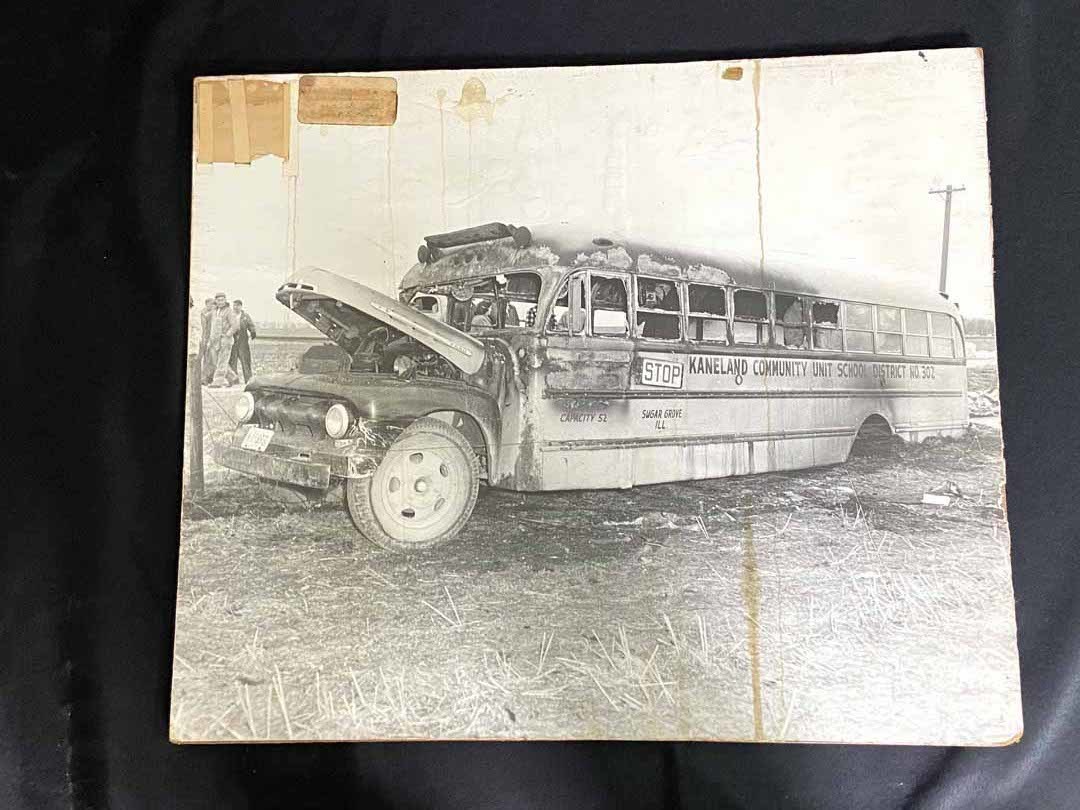

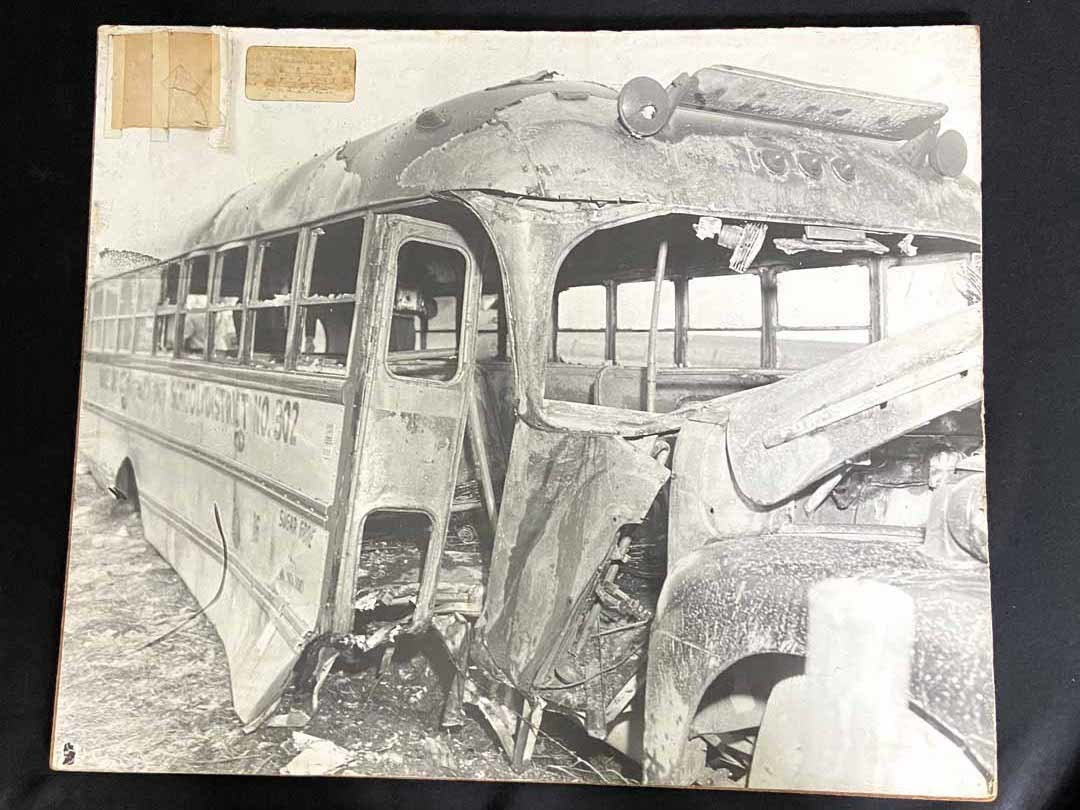

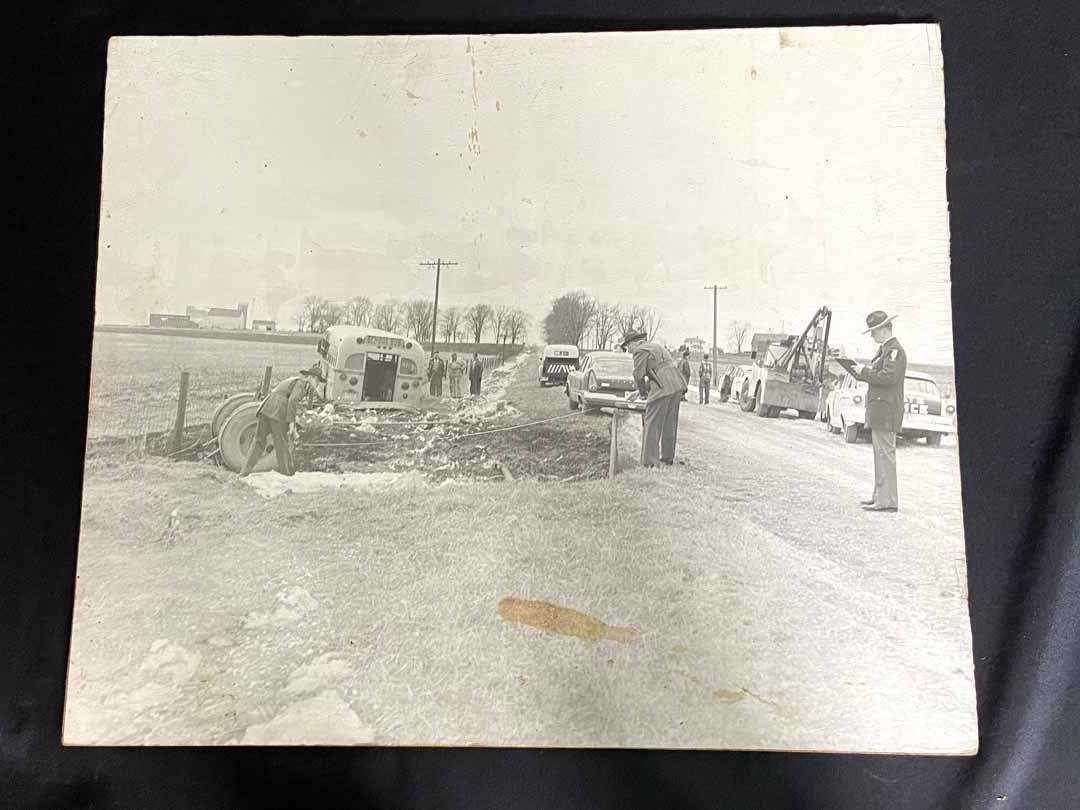

On March 10, 1958, a school bus of the Kaneland School District struck a culvert, exploded and burned, causing injuries and burns to 14 of the children who were passengers in the bus.

Suits were filed against the school district on behalf of the injured children, including the four Molitor children and the other four children who are all plaintiffs herein.

Motions to dismiss the complaints which omitted the allegation of insurance were filed by the school district.

…

The circuit court of Kane County dismissed the common-law negligence counts of plaintiffs' complaints against defendant Kaneland Community Unit District No. 302. The Appellate Court affirmed the judgments of dismissal on the ground that they were based on an accident occurring prior to December 16, 1959…

…

[The case was then brought to the Supreme Court of Illinois who found the following:] Hence the counts omitting the allegation of insurance in plaintiffs' complaints should not have been dismissed, and the judgments are reversed and the causes remanded to the trial court, with directions to reinstate the counts.

Reversed and remanded, with directions.

24 Ill. 2d 467 (1962)

Supreme Court of Illinois.

Opinion filed March 23, 1962.

On March 10, 1958, a school bus of the Kaneland School District struck a culvert, exploded and burned, causing injuries and burns to 14 of the children who were passengers in the bus.

Suits were filed against the school district on behalf of the injured children, including the four Molitor children and the other four children who are all plaintiffs herein.

Motions to dismiss the complaints which omitted the allegation of insurance were filed by the school district.

…

The circuit court of Kane County dismissed the common-law negligence counts of plaintiffs' complaints against defendant Kaneland Community Unit District No. 302. The Appellate Court affirmed the judgments of dismissal on the ground that they were based on an accident occurring prior to December 16, 1959…

…

[The case was then brought to the Supreme Court of Illinois who found the following:] Hence the counts omitting the allegation of insurance in plaintiffs' complaints should not have been dismissed, and the judgments are reversed and the causes remanded to the trial court, with directions to reinstate the counts.

Reversed and remanded, with directions.

Description

SOURCE: Molitor v. KANELAND UNIT DIST. NO. 302

24 Ill. 2d 467 (1962)

182 N.E.2d 145

NORMA MOLITOR et al., Appellants, v. KANELAND COMMUNITY UNIT DISTRICT NO. 302, Appellee.

No. 36588.

Supreme Court of Illinois.

Opinion filed March 23, 1962.

Rehearing denied May 23, 1962.

REID, OCHSENSCHLAGER, MURPHY & HUPP, and GIVLER, MEILINGER & CASEY, both of Aurora, (DALE C. FLANDERS, of counsel,) for appellants.

MATTHEWS, JORDAN, DEAN & SUHLER, of Aurora, BURRELL & HOLTAN, of Freeport, and CARBARY & CARBARY, of Elgin, (JOHN T. MATTHEWS, DAVID M. BURRELL, and ROGER W. EICHMEIER, of counsel,) for appellee.

HAROLD W. NORMAN, of Chicago, for Illinois Association of School Boards, amicus curiae.

FRANK R. SCHNEBERGER, DAVID S. KERWIN, and KIRKLAND, ELLIS, HODSON, CHAFFETZ & MASTERS, all of Chicago, *468 (THOMAS F. SCULLY, of counsel,) for the Board of Education of the City of Chicago, and the Chicago Park District, amici curiae.

Reversed and remanded.

Mr. JUSTICE KLINGBIEL delivered the opinion of the court:

The circuit court of Kane County dismissed the common-law negligence counts of plaintiffs' complaints against defendant Kaneland Community Unit District No. 302. The Appellate Court affirmed the judgments of dismissal on the ground that they were based on an accident occurring prior to December 16, 1959 and were, therefore, barred by our decision in Molitor v. Kaneland Community Unit Dist. 18 Ill. 2d 11. A certificate of importance was then issued to this court.

On March 10, 1958, a school bus of the Kaneland School District struck a culvert, exploded and burned, causing injuries and burns to 14 of the children who were passengers in the bus. Suits were filed against the school district on behalf of the injured children, including the four Molitor children and the other four children who are all plaintiffs herein. Motions to dismiss the complaints which omitted the allegation of insurance were filed by the school district.

That there was uncertainty as to whether the dismissal would be upheld by this court is apparent. The claims of all the Molitor children had been set forth in one complaint. To expedite review and minimize expense, the trial court suggested "going up on a short record at an early date, on the sole question of whether the complaint states a good cause of action," and that this would provide "the basis for determining the future course of the parties to this case as well as other claimants." The count on behalf of Thomas Molitor, whose name was selected arbitrarily for the appeal, was dismissed. After Thomas Molitor had elected to stand by his complaint, amended complaints were *469 filed on behalf of the other children on September 2, 1958. As to each child the amended complaint reiterated the original complaint in one count, and in another alleged the existence of insurance. The record now before us shows that motions to dismiss those counts which repeated the allegations of the original complaint were filed, but were permitted to remain dormant until July of 1960. The cost of the Thomas Molitor appeal and the payment of counsel was borne by the Molitor children and the other plaintiffs through their parents. Thus, it is now clear that in the trial court the parties envisaged adjudication of the appeal by Thomas Molitor as determining the ruling to be made on the motions to dismiss the complaints of the plaintiffs.

The initial opinion on that appeal, entered May 22, 1959, abrogated the doctrine of tort immunity of school districts, but contained no restriction on its retroactive application. We then granted the requests of the Chicago Park District, the Illinois Association of School Boards, the Board of Education of the City of Chicago, and the Forest Preserve District to intervene and to file briefs as amici curiae. These organizations not only reargued the retention of the immunity rule, but they asserted that the new rule should be applied prospectively to obviate undue hardship upon them.

Upon rehearing, this court on December 16, 1959, issued its final opinion reported in 18 Ill. 2d 11 abolishing tort immunity of school districts and expressly provided that "except as to the plaintiff in the instant case, the rule herein established shall apply only to cases arising out of future occurrences." (18 Ill. 2d 11, 26-7.) Prospective application was invoked because school districts had justifiably relied upon prior decisions of this court and had failed to insure and to investigate past accidents, especially as to minors against whom the Statute of Limitations had not yet run. The new ruling was nevertheless applied there to obviate any implication that the ruling was dictum and to preserve the *470 incentive of litigants to challenge out-moded or erroneous rules of law.

The immunity granted to school districts is not an absolute one and can be waived. (Thomas v. Broadlands Community Consolidated School Dist. 348 Ill. App. 567.) While there was no written stipulation that the rule applied in the Thomas Molitor appeal would be the basis for determining the cases then pending against defendant, the conduct of all parties and the trial court reveal that it was commonly understood and accepted that this court's ruling on the dismissal of Thomas Molitor's claim would be the basis for determining the other claims arising out of the same bus accident and then pending against defendant. The ruling on the Thomas Molitor claim was, of course, that the motion to dismiss based on governmental immunity should be denied. Because it now appears the Thomas Molitor appeal was treated by the parties as a test case for determining what ruling should ultimately be made, we hold that the counts in question should not have been dismissed.

It should be evident that this holding in no way modifies or affects our holding in the Molitor case or the cut-off date relative to governmental tort immunity as previously established in that case, and therefore, does not interfere with the rights of any of the amici curiae in this case. Nor, does this holding affect the intervening decisions of Peters v. Bellinger, 19 Ill. 2d 367, or List v. O'Connor, 19 Ill. 2d 337. We are dealing here only with claims which, as clearly appears from the record now before us, the parties contemplated would be adjudicated in accordance with the disposition of the claim of Thomas Molitor. Hence the counts omitting the allegation of insurance in plaintiffs' complaints should not have been dismissed, and the judgments are reversed and the causes remanded to the trial court, with directions to reinstate the counts.

Reversed and remanded, with directions.

*****

SOURCE: Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, Volume 2, Issue 1, Winter 1971, Article 6, Illinois School Tort Immunity, 1959—Present”

In Illinois, the court acted first. The final decision of Molitor v. Kaneland Community Unit District was rendered December 16, 1959. Until that time, pursuant to the decision in Kinnare, schools and school districts enjoyed complete immunity from tort liability in all cases except those where liability insurance had been purchased. The Molitor decision overruled Kinnare, and held that where a school district employee had been negligent in the operation of a school bus which resulted in injury to the plaintiff, the school district was liable in tort. The court declared, "We conclude that the rule of school district immunity is unjust, unsupported by any valid reason, and has no rightful place in modem-day society."' The rationale of the decision was based on a reappraisal, in light of "modem-day society," of the sovereign immunity defenses that the "king can do no wrong," and that the payment of tort claims was an improper diversion of public education funds. This persistent view of funds being "diverted" by the recovery of damages in tort was rejected because no determination had ever been made by a court as to what a proper school expenditure was. The relationship between the school's purpose and its financial responsibility for the negligent execution of that purpose had not been as clearly drawn as it had in business activities. "To predicate immunity upon the theory of a trust fund [for example] is merely to argue in a cricle, since it assumes an answer to the very question at issue, what is an educational purpose? ‘

In repudiation of the "king can do no wrong" theory, the court said: It is almost incredible that in this modem age . . . the mideaval absolutism implicit in the maxim, "the king can do no wrong"

should exempt the various branches of government from liability for their torts, and that the entire burden of damage resulting from the wrongful acts of the government should be imposed upon the single individual who suffers the injury, rather, than distributed among the entire community... In rebuttal to the charge such liability would "bankrupt" schools and school districts and impede education, the court declared that: We do not believe, in this day and age, when public education constitutes one of the biggest businesses in the country, that school immunity can be justified on the protection-of-public-funds theory . . . Private concerns have rarely been greatly embarrassed, and in no instance, even where immunity is not recognized, has a municipality been seriously handicapped by tort liability. Citing Dean Green the court said: The public's willingness to . . . pay the cost of its enterprises . . . through municipal corporations is no less than its insistence that individuals and groups pay the cost of their enterprises. The court claimed the ability to make so sweeping a decision in the face of legislative inactivity because: The doctrine of school tort immunity was created by this court alone. Having found that doctrine to be unsound and unjust under present conditions, we consider that we have not only the power, but the duty to abolish that immunity. Although the final Molitor decision made a clean break with the past, and eliminated sovereign immunity from tort, the legislature acted to modify the effects of the decision.

…

III. THE 1959 SCHOOL TORT LIABILITY ACT Prior to Molitor, a proprietary-governmental distinction had been drawn with respect to the sovereign immunity of municipal corporations. When the court in Molitor abolished the sovereign immunity of any political subdivision of the state it rendered this distinction moot. In reaction to Molitor, the legislature enacted the 1959 School Tort Liability Act. It applied the proprietary--governmental distinction to schools and school districts, making them totally immune from tort liability for their governmental functions and limited their tort liability for proprietary functions to a maximum of $10,000.50

24 Ill. 2d 467 (1962)

182 N.E.2d 145

NORMA MOLITOR et al., Appellants, v. KANELAND COMMUNITY UNIT DISTRICT NO. 302, Appellee.

No. 36588.

Supreme Court of Illinois.

Opinion filed March 23, 1962.

Rehearing denied May 23, 1962.

REID, OCHSENSCHLAGER, MURPHY & HUPP, and GIVLER, MEILINGER & CASEY, both of Aurora, (DALE C. FLANDERS, of counsel,) for appellants.

MATTHEWS, JORDAN, DEAN & SUHLER, of Aurora, BURRELL & HOLTAN, of Freeport, and CARBARY & CARBARY, of Elgin, (JOHN T. MATTHEWS, DAVID M. BURRELL, and ROGER W. EICHMEIER, of counsel,) for appellee.

HAROLD W. NORMAN, of Chicago, for Illinois Association of School Boards, amicus curiae.

FRANK R. SCHNEBERGER, DAVID S. KERWIN, and KIRKLAND, ELLIS, HODSON, CHAFFETZ & MASTERS, all of Chicago, *468 (THOMAS F. SCULLY, of counsel,) for the Board of Education of the City of Chicago, and the Chicago Park District, amici curiae.

Reversed and remanded.

Mr. JUSTICE KLINGBIEL delivered the opinion of the court:

The circuit court of Kane County dismissed the common-law negligence counts of plaintiffs' complaints against defendant Kaneland Community Unit District No. 302. The Appellate Court affirmed the judgments of dismissal on the ground that they were based on an accident occurring prior to December 16, 1959 and were, therefore, barred by our decision in Molitor v. Kaneland Community Unit Dist. 18 Ill. 2d 11. A certificate of importance was then issued to this court.

On March 10, 1958, a school bus of the Kaneland School District struck a culvert, exploded and burned, causing injuries and burns to 14 of the children who were passengers in the bus. Suits were filed against the school district on behalf of the injured children, including the four Molitor children and the other four children who are all plaintiffs herein. Motions to dismiss the complaints which omitted the allegation of insurance were filed by the school district.

That there was uncertainty as to whether the dismissal would be upheld by this court is apparent. The claims of all the Molitor children had been set forth in one complaint. To expedite review and minimize expense, the trial court suggested "going up on a short record at an early date, on the sole question of whether the complaint states a good cause of action," and that this would provide "the basis for determining the future course of the parties to this case as well as other claimants." The count on behalf of Thomas Molitor, whose name was selected arbitrarily for the appeal, was dismissed. After Thomas Molitor had elected to stand by his complaint, amended complaints were *469 filed on behalf of the other children on September 2, 1958. As to each child the amended complaint reiterated the original complaint in one count, and in another alleged the existence of insurance. The record now before us shows that motions to dismiss those counts which repeated the allegations of the original complaint were filed, but were permitted to remain dormant until July of 1960. The cost of the Thomas Molitor appeal and the payment of counsel was borne by the Molitor children and the other plaintiffs through their parents. Thus, it is now clear that in the trial court the parties envisaged adjudication of the appeal by Thomas Molitor as determining the ruling to be made on the motions to dismiss the complaints of the plaintiffs.

The initial opinion on that appeal, entered May 22, 1959, abrogated the doctrine of tort immunity of school districts, but contained no restriction on its retroactive application. We then granted the requests of the Chicago Park District, the Illinois Association of School Boards, the Board of Education of the City of Chicago, and the Forest Preserve District to intervene and to file briefs as amici curiae. These organizations not only reargued the retention of the immunity rule, but they asserted that the new rule should be applied prospectively to obviate undue hardship upon them.

Upon rehearing, this court on December 16, 1959, issued its final opinion reported in 18 Ill. 2d 11 abolishing tort immunity of school districts and expressly provided that "except as to the plaintiff in the instant case, the rule herein established shall apply only to cases arising out of future occurrences." (18 Ill. 2d 11, 26-7.) Prospective application was invoked because school districts had justifiably relied upon prior decisions of this court and had failed to insure and to investigate past accidents, especially as to minors against whom the Statute of Limitations had not yet run. The new ruling was nevertheless applied there to obviate any implication that the ruling was dictum and to preserve the *470 incentive of litigants to challenge out-moded or erroneous rules of law.

The immunity granted to school districts is not an absolute one and can be waived. (Thomas v. Broadlands Community Consolidated School Dist. 348 Ill. App. 567.) While there was no written stipulation that the rule applied in the Thomas Molitor appeal would be the basis for determining the cases then pending against defendant, the conduct of all parties and the trial court reveal that it was commonly understood and accepted that this court's ruling on the dismissal of Thomas Molitor's claim would be the basis for determining the other claims arising out of the same bus accident and then pending against defendant. The ruling on the Thomas Molitor claim was, of course, that the motion to dismiss based on governmental immunity should be denied. Because it now appears the Thomas Molitor appeal was treated by the parties as a test case for determining what ruling should ultimately be made, we hold that the counts in question should not have been dismissed.

It should be evident that this holding in no way modifies or affects our holding in the Molitor case or the cut-off date relative to governmental tort immunity as previously established in that case, and therefore, does not interfere with the rights of any of the amici curiae in this case. Nor, does this holding affect the intervening decisions of Peters v. Bellinger, 19 Ill. 2d 367, or List v. O'Connor, 19 Ill. 2d 337. We are dealing here only with claims which, as clearly appears from the record now before us, the parties contemplated would be adjudicated in accordance with the disposition of the claim of Thomas Molitor. Hence the counts omitting the allegation of insurance in plaintiffs' complaints should not have been dismissed, and the judgments are reversed and the causes remanded to the trial court, with directions to reinstate the counts.

Reversed and remanded, with directions.

*****

SOURCE: Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, Volume 2, Issue 1, Winter 1971, Article 6, Illinois School Tort Immunity, 1959—Present”

In Illinois, the court acted first. The final decision of Molitor v. Kaneland Community Unit District was rendered December 16, 1959. Until that time, pursuant to the decision in Kinnare, schools and school districts enjoyed complete immunity from tort liability in all cases except those where liability insurance had been purchased. The Molitor decision overruled Kinnare, and held that where a school district employee had been negligent in the operation of a school bus which resulted in injury to the plaintiff, the school district was liable in tort. The court declared, "We conclude that the rule of school district immunity is unjust, unsupported by any valid reason, and has no rightful place in modem-day society."' The rationale of the decision was based on a reappraisal, in light of "modem-day society," of the sovereign immunity defenses that the "king can do no wrong," and that the payment of tort claims was an improper diversion of public education funds. This persistent view of funds being "diverted" by the recovery of damages in tort was rejected because no determination had ever been made by a court as to what a proper school expenditure was. The relationship between the school's purpose and its financial responsibility for the negligent execution of that purpose had not been as clearly drawn as it had in business activities. "To predicate immunity upon the theory of a trust fund [for example] is merely to argue in a cricle, since it assumes an answer to the very question at issue, what is an educational purpose? ‘

In repudiation of the "king can do no wrong" theory, the court said: It is almost incredible that in this modem age . . . the mideaval absolutism implicit in the maxim, "the king can do no wrong"

should exempt the various branches of government from liability for their torts, and that the entire burden of damage resulting from the wrongful acts of the government should be imposed upon the single individual who suffers the injury, rather, than distributed among the entire community... In rebuttal to the charge such liability would "bankrupt" schools and school districts and impede education, the court declared that: We do not believe, in this day and age, when public education constitutes one of the biggest businesses in the country, that school immunity can be justified on the protection-of-public-funds theory . . . Private concerns have rarely been greatly embarrassed, and in no instance, even where immunity is not recognized, has a municipality been seriously handicapped by tort liability. Citing Dean Green the court said: The public's willingness to . . . pay the cost of its enterprises . . . through municipal corporations is no less than its insistence that individuals and groups pay the cost of their enterprises. The court claimed the ability to make so sweeping a decision in the face of legislative inactivity because: The doctrine of school tort immunity was created by this court alone. Having found that doctrine to be unsound and unjust under present conditions, we consider that we have not only the power, but the duty to abolish that immunity. Although the final Molitor decision made a clean break with the past, and eliminated sovereign immunity from tort, the legislature acted to modify the effects of the decision.

…

III. THE 1959 SCHOOL TORT LIABILITY ACT Prior to Molitor, a proprietary-governmental distinction had been drawn with respect to the sovereign immunity of municipal corporations. When the court in Molitor abolished the sovereign immunity of any political subdivision of the state it rendered this distinction moot. In reaction to Molitor, the legislature enacted the 1959 School Tort Liability Act. It applied the proprietary--governmental distinction to schools and school districts, making them totally immune from tort liability for their governmental functions and limited their tort liability for proprietary functions to a maximum of $10,000.50

Identifier

1992-59D, 1992-59F, 1992-59B, 1992-59E, 1992-59C

Date

1958, 1962

Creator

Kaitlin

Language

[no text]

Rights

[no text]

Format

[no text]

Relation

[no text]

Source

https://law.justia.com/cases/illinois/supreme-court/1962/36588-5.html

https://lawecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2481&context=luclj

https://lawecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2481&context=luclj

Publisher

[no text]

Contributor

[no text]

Type

[no text]

Coverage

[no text]